In November 2016, I visited South Africa to attend BLACK PORTRAITURE[S] III: Reinventions: Strains of Histories and Cultures. Hosted by NYU Tisch School of the Arts in conjunction with other American and South African institutions, BLACK PORTRAITURE[S] is a 3-day conference that brings together artists, academics and activists to discuss the complexities of black histories and identities through art.

The conference was fittingly hosted in Johannesburg, a city troubled with a painful history of apartheid and its colonial legacies, but bursting with so much creativity, culture and activism.

To say the conference was incredible is a severe understatement. I was bursting with excitement the minute I entered Turbine Hall on Thursday morning, eagerly waiting for the introductory remarks in a room full of people from around the world.

Designer Maria McCloy, photographer Trevor Stuurman, creative consultant Malcolm Ché, trend analyst Nicola Cooper and designer Chularp Suwannapha speaking on the panel "Preservation of African Fashion from Global Mis-appropriation" hosted by Oxosi.com

I could not believe that I was surrounded by so many people who cared about black identity, activism and art, and the simple fact that a conference like this exists left me with so much vindication for my work.

Over the three days, I got to listen to, learn from and participate in discussions on a vast range of topics including, but certainly not limited to, representations of the black female body in art, the role of photography in colonialism and whether or not the circulation of violent images of black bodies is a necessary part of educating our communities about our suppressed histories.

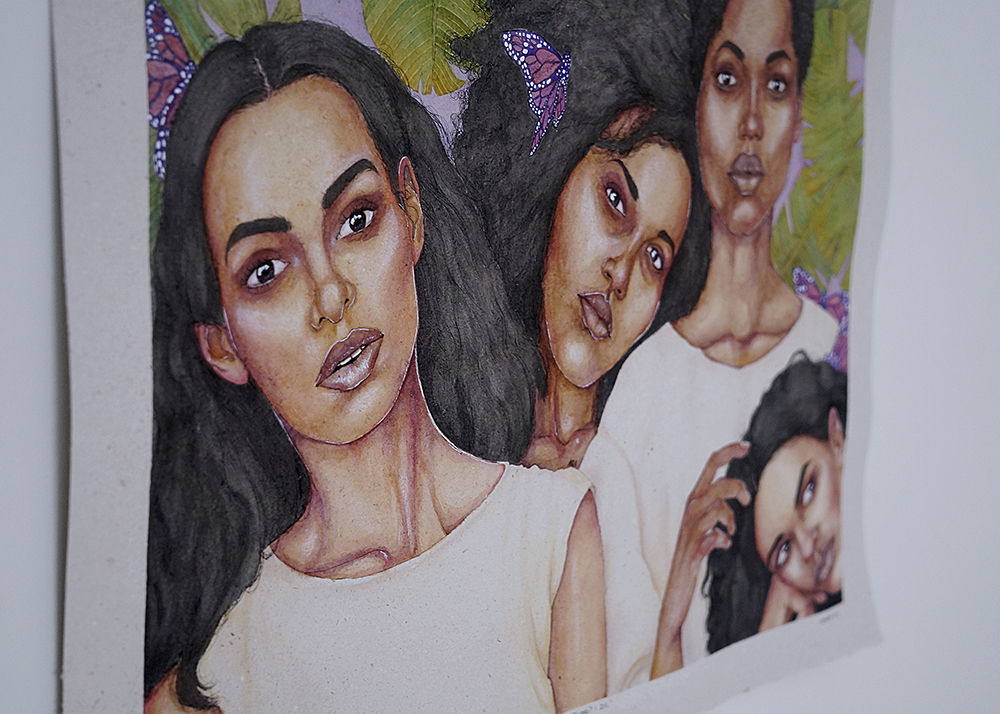

The panelists were open to being challenged, which encouraged fervent debates long after formal discussions were closed. I got to speak with some of my favourite women artists (such as Nontsikelelo Mutiti, Rharha Nembhard, Lina Iris Viktor and Zanele Muholi) and was introduced to the work of dozens more (such as Heather Agyepong, Helina Metaferia, Jordan Casteel and Kenyatta A.C. Hinkle).

The revolutionary act of centralizing our own voices (even when we don't necessarily agree) cannot be stated enough. I left the conference with an immense sense of pride, belonging and inspiration, ready to build the future we all so dearly hoped for.

Artists Ebony G. Patterson, Noel Anderson, Rashad Newsome and Jordan Casteel speak about their works on the panel "Portrait as Politic" moderated by the Studio Museum in Harlem

Writer Milisuthando Bongela beautifully moderates the panel "Universal Blackness: The Black Diaspora Experience in the 21st Century presented by ARTNOIR" with artists Nontsikelelo Mutiti (left) and Lina Iris Viktor (right)